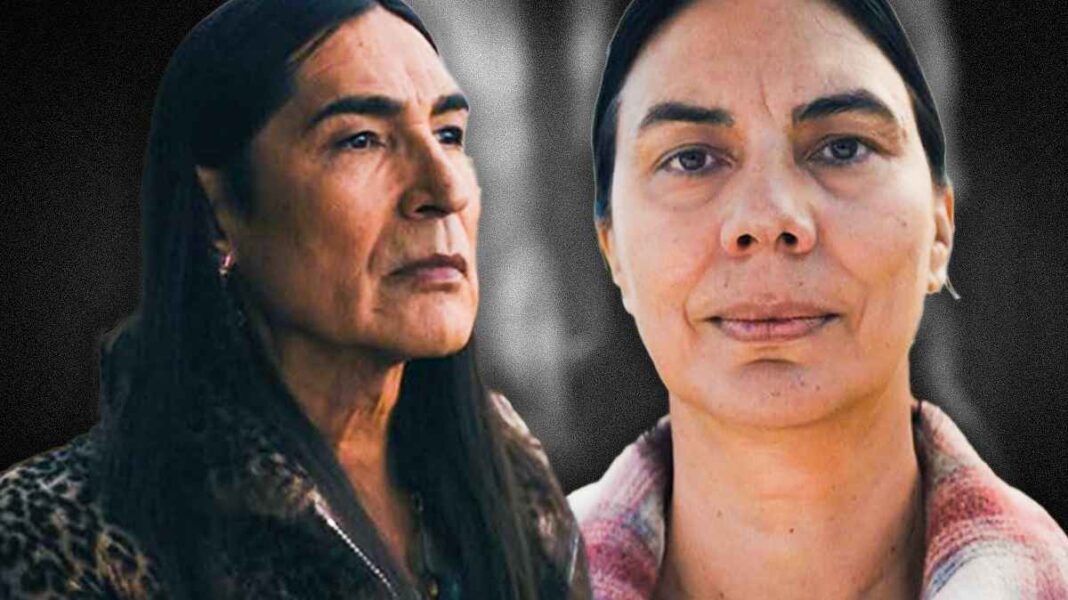

“Aberdeen,” directed by Eva Thomas and Ryan Cooper, is the story of an Indigenous woman from Canada, who is thrown into a quagmire when she loses all her identification cards. The eponymous protagonist of the film, Aberdeen, is forced to deal with the inhospitable authorities, changing climate, stringent state foster care, and estranged relatives all at once, with no sign of mercy. As we see Aberdeen trying to scream her way out of her problems, we are forced to realize that the very system that germinates the seeds of her anger also has the power to throttle her voice. She is heckled, picked up by the police, abused, and threatened but none of the maltreatment can ensure the restoration of her basic rights.

Will Aberdeen be released from the drunk tank?

In Winnipeg, Aberdeen Spence lands up in the drunk tank for getting into a scuffle with a police officer while completely drunk. As she tries to flee the scene, she loses the plastic zipped bag containing all her important docs and IDs. Aberdeen’s brother, Boyd, manages to get her a release. Boyd also reveals to her that he is unable to continue looking after her kids and grandchildren as he has been diagnosed with cancer, and he has surrendered them to foster care. Boyd pleads with Aberdeen, who is now homeless after being thrown out of her last motel, to return home. Aberdeen is not too confident and is constantly reminded of her daughter, who has ended up a drug addict. Furthermore, when her grandchildren are placed in the care of a White family, Aberdeen turns livid.

With the help of her friends, Aberdeen scans through the entire locality in search of the IDs. She moves from the tent city to the motel where she last stayed.

The prevailing discrimination against First Nations people

“Aberdeen” is a painful account of how steadily the bureaucracy debases the dignity of the Indigenous people. The misjudged notion about their ungovernable nature continues to cast a shadow over the communities. Oppressive and discriminatory state policies make day to day life harrowing for Aberdeen and her like. For Aberdeen, landing up in the drunk tank and securing a status card exact the same toll, mentally and physically. We watch in apprehension as she is forced to drag herself from door to door in search of some leads for obtaining her ID proof.

The bureaucratic system is nonchalant towards people like Aberdeen. It already assumes that the Indigenous all over are criminally inclined and, therefore, not worthy of trust. The sense of hostility that permeates the environment is immediately palpable. The second assumption stems from this intolerance and likes to imagine the Indigenous as being unworthy of familial ties. There is a point in the film where Aberdeen is turned away when she goes to pick her treaty money. In a drunken stupor, she scuttles towards the Canadian Indigenous Affairs Office for a second time and launches into an angry diatribe against the authority. Rather than Aberdeen’s anger being a sign of her own internal issues and a commentary on the unruliness of her community, the film tries to trace her agitation to the generational trauma meted out to her people by the government. When Aberdeen angrily stomps the ground trying to reclaim her rights, she is perceived as nothing more than a lunatic drunkard, and her concerns are all delusional tomfoolery. It is not until she meets Grace that she secures a duplicate ID.

Aberdeen quite obviously is not allowed to have her grandchildren due to not having permanent housing or any source of income. The lady at the foster home states clearly that Aberdeen is incapable of taking on caregiver duties if she does not work towards becoming sober. Both Aberdeen and her daughter, Pritchard, are pronounced as unsafe for the kids for the time being. Aberdeen’s friend, Alfred, accompanies her to the Indigenous Affairs Office once again to help her secure a status card. Witnessing her desperation, Alfred advises it’s best to play along with the system’s rules. Later, Aberdeen has a falling out with Alfred, who accuses the former of being unmindful of the way she is putting the lives of others around her in jeopardy.

Where does Aberdeen find her status card?

Heartbroken over Alfred’s words and the condition of her family, she tries to jump off a bridge, but a stranger clutches onto Aberdeen and saves her. We recognize the man to be the one who picked up the IDs on the day Aberdeen was running away from the police. Aberdeen realizes that she has a shared history with the man from Peguis. The man hands her the lost status card and tells her that he had been holding onto it just to give it to her. Upon receiving the card, she wastes no time and arrives at Pritchard’s house to talk about the possibility of her getting back the kids. However, her story does not have a happy ending, as Pritchard has already died of an overdose. Aberdeen is engulfed by self-pity over her disappointing role as a caregiver for her own daughter. Boyd tries to keep her from spiralling, and it is now that Aberdeen gets over her initial fear of adopting the children and becomes certain of the importance of them having a guardian figure in their lives. Aberdeen has witnessed the ruinous effects of a life gone astray, so while she has time, she tries to reverse the wheel and the prolonged damage inflicted on her grandkids.

In the end, Aberdeen is ready to start her life afresh with the man who saved her life. Before she can take in the children, she is ready to go into the rehabilitation center for women and asks the foster lady for the number. This simple act shows the changes inside Aberdeen that have come from rigorous introspection. It is never someone else choosing what is best for her, but Aberdeen being an agent of her choices. It can be anticipated that Aberdeen’s informed choice would only prove to be the healthiest and the most fruitful decision for the kids in the long run.