No matter how many times a reader comes across the age-old saying, “Do not judge a book by its cover,” there are times when it is purposefully and safely ditched for all the right reasons. “Manto and Chughtai: The Essential Stories,” published in 2019 by Penguin, is one such classic case in point. Translated to English from the original Urdu, this book is a collection of short stories by two eminent writers of Urdu fiction set in the pre-partition Indian subcontinent.

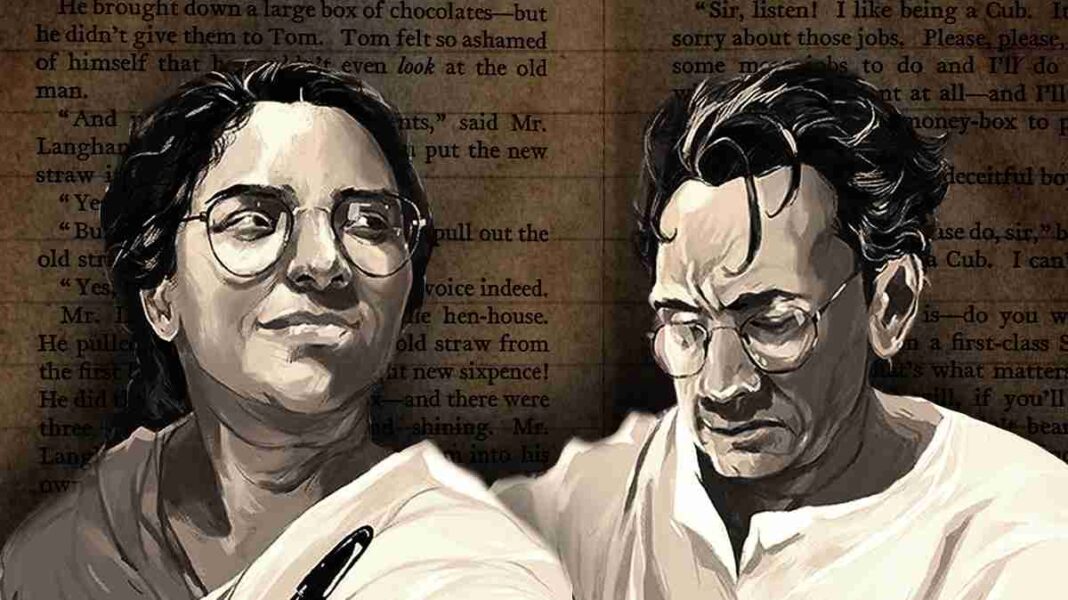

Saadat Hasan Manto’s short stories are translated by Muhammad Umar Menon, and Ismat Chughtai’s short stories are translated by M. Asaduddin. The ornately done book covers are available in flip style, with the portraits of both authors in colored and detailed pencil drawings. It means that half the book has selected stories of Saadat Hasan Manto, and when the book is flipped to the other end of the cover, it starts afresh and covers the rest of the books with the stories of Ismat Chughtai. This gives the notion of two books in one. Perhaps one of the firsts by Penguin Publishers, this uniquely thoughtful presentation is inked in blue and pink against a backdrop of golden leaves, vines, and stem artistry that evokes a delicate style. It adds a touch of intricacy and subtlety that portrays the stature and grandeur of the writing of both the aforementioned authors. However, other than the covers, the rest of the text is rather black and white, but it is the content that creates the spark.

For the uninitiated, the book serves as an introduction to a literary genre and literary range that is robust yet subtle but undoubtedly frank, bold, revolutionary, and reformatory, and has an openness imbibed with a keen sense of being courageous enough to speak out loud about the social ills of the time in which it is set. Both authors were known for having the spine to stand up for one’s rightful viewpoint with the intention to, in turn, bring about the betterment of society. This was the quintessential mark of the Progressives. However, the book does not require the reader to have any pre-requisite knowledge about the Progressive Writers Association (PWA) and its literary history, though a basic understanding of the PWA’s contribution will be beneficial. Nonetheless, even with the lack of knowledge about the effect that the PWA had on the literary scenario of the subcontinent, the collection of short stories is such that it does not deter a reader from being able to follow through, but it calls for a lot of attentive reading so as to be able to decipher the underlying encrypted ideas that the stories convey.

The plotlines of the short stories mainly revolve around themes like interfaith relationships, societal pressure, religious bias, stereotyping, communal violence, the low status of women, sex, sexuality, desire, and an array of emotional turmoil that marks interpersonal relationships, particularly romantic relationships. The plots vary in pace. They seem to pick up pace at certain points and slow down at others. Either way, the plots are instrumental in capturing the essence of the time, the struggles of society, the wishes of individuals, and the overall position of socio-cultural development under a changing social order. The length of the stories is moderate. They are neither too long nor too short. At most, they cover 5–6 pages of engrossing plot twists that make for an unpredictably exceptional read. However, a short introduction to each short story would have made the book more reader-friendly, specifically for those who are reading for the first time. A contextual interpretation, along with the social history in which the stories are set, could be included to add to the multi-dimensional perspectives that can be drawn from these stories. This will also improve the reader’s capacity to understand the stories better, to delve into their thematic significance, and to feel the plots deeply.

Additionally, this may also serve to help readers assess and appreciate the capabilities of the authors in highlighting several issues through simple, everyday characters. This marks a writing style that is quite different in the case of Manto and Chughtai but has its roots in the notion of social justice and voicing the unvoiced, or rather, that which is considered a social taboo or stigma. While Chughtai has a subtle sense of humor, a keen eye for the little details, and a unique way of shattering the bounds of conservatism or patriarchy, Manto has an aura that is rather angry at the state of affairs, saddened, and deeply engrossed in calling for change for the better. Yet, what marks their writing is the sense of social responsibility that education and a love for education engrave in the minds of the truly learned.

It is the ability to discuss, delineate, and debate. Yet, at no point in their work do they dictate the solution. Rather, they advocate for change through the collective realization of the flaws of human society. These flaws form the core of the significant characters in their stories. The characters are simple people, making them relatable, and they are drawn with a realism that makes them lifelike. Such realism is equipped with not just honest depiction but also an overall authorial ability to convey their thoughts, views, and opinions with literary artistry. It is hard to say or pick one short story over the other, as the selections in this book are aptly done to bring forth some of the best works of both authors. At 224 pages, the book is a moderately lengthy read, but clearly not one that can be covered in a short span of time. This book calls for extensive reading and re-reading between the lines to fully enjoy the multi-faceted prowess of both authors. This makes the reading process engaging and engrossing. This book will be of interest to lovers of partition literature, short story enthusiasts, realistic fiction fans, and those interested in reading Urdu fiction in translation.